Victor asks for tips in dealing with pests and other natives of the Appalachian Trail, such as Ticks, Flies, Mice, Poison Oak, Poison Ivy, and any others not on his radar. I’m going to break his question up in parts.

First, let me just remind you that Victor's hike begins this Thursday (March 28th), join me in following his progress at BackpackingAT.com.

VM: From what I hear, knowledge is power. Is it true that learning how to prevent visitors is half the battle, or is it inevitable?

RG: Yes and yes. There are ways to reduce potential issues with the bugs and wildlife, but it comes with the territory. There are different guidelines for different pests that I’ll go into below.

Ticks

Ticks

VM: Do you have any useful hints for removing ticks? Is it true a drop of turpentine will make the ticks dig themselves out?

RG: Good question. Ticks are the worst. I'd honestly rather see a black bear on the trail (actually I love seeing black bears, so that's a bad example). I only saw two ticks crawling on me while hiking the AT, but I also met two hikers who contracted Lyme Disease, so it's good to know a few things about them before heading out.

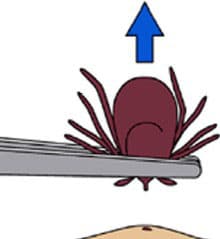

There are several myths about tick prevention and removal. Using heat or covering the tick with anything in order to coax it back out can only make the problem worse. It can actually cause them to regurgitate more saliva (and potentially more pathogens) into your bloodstream.

The hypostome, i.e. mouth parts, that they burrow into your skin, looks similar to a tiny barbed harpoon. Also, some ticks, like the Lyme-Disease-spreading deer tick, secrete a cement-like substance to keep themselves securely attached to your skin while feeding. In other words, they can't back out quickly even if they wanted to. The longer the tick is attached, the higher your risk of infection, so the goal is to remove the tick as soon as possible.

The best way to remove a tick

The best way is with tweezers. Some ticks, like the Deer Tick, can be as tiny as a poppy seed, so you’ll need tweezers that can grab something that small. Grab the tick as close to your skin as possible and slowly pull it straight out. Clean the skin around the bite with alcohol. If the hypostome (mouthparts) remain stuck in your skin, don’t worry about it. Doctors aren't concerned about it, so I'm not either. Also, when the hypostome breaks it may even send germs and saliva further back into the ticks body and saliva glands.

Lyme Disease

The biggest concern with ticks on the Appalachian Trail is Lyme Disease. There are 30,000 to 40,000 cases in the United States annually and about three out of four are reported in ten of the states along the Appalachian Trail.

Here they are in order of highest cases per capita: Vermont, New Hampshire, Maine, Connecticut, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Massachusetts, Maryland, New York, and Virginia.

Here they are in order of highest cases per capita: Vermont, New Hampshire, Maine, Connecticut, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Massachusetts, Maryland, New York, and Virginia.

If you experience any symptoms like a rash or fever, consult your doctor and let them know you've been bitten.

Preventing Ticks

Chances are you'll hike the entire Appalachian Trail without having a tick burrow into you, but with a few precautions, you can reduce your risk of getting Lyme Disease to nearly zero.

Do a daily tick check

Full disclosure, the longer I went without seeing a tick the less frequently I would do a tick check. Eventually, I only checked after hiking through bushy areas with tall grass or loose dry leaves on the ground. My laziness aside, daily checks are by far the best way to prevent the spread of Lyme Disease. It generally takes at least 24-48 hours for a tick to transmit the disease, so if you're doing daily checks, it's unlikely you'll get it.

Thorough tick checks are important since their saliva has anesthetic properties. That means you won't feel them burrowing or feeding. Additionally, they are hard to find because some, like the deer tick, are as small as a fleck of dirt, which you'll be covered in most of the time. They also have a tendency to search for places on your body that are hard to see without a mirror... and places your friends will not volunteer to check for you.

Bug Repellent

I'll go into this deeper below, but DEET is still the most effective bug repellent. Nothing really comes close in effectiveness, duration of effectiveness, and cost per ounce. There are a lot of home remedy bug repellent myths out there, but none have been shown to be effective for more than a few minutes, if effective at all. Don't waste your time or risk going without an effective treatment. A 23 to 33% DEET solution is the way to go and it's safe if used properly.

Wear Light Colored Clothing

Even though I didn't have any biting ticks on the Appalachian Trail, I did find a couple crawling on my pant legs. It happened after scouring the woods for firewood in Shenandoah National Park. Since I wore light brown khaki pants they were easy to spot.

Walk in the center of trails

Those minuscule SOBs are hanging onto plants with their little legs outstretched waiting for a blood-filled mammal to walk by. Avoid their reach by walking down the center of the trail whenever possible.

Some months are worse than others

Peak tick season starts in late-April to early-May and lasts all through summer. That doesn't mean you won’t get ticks on you in October, though. Actually, that's when I found them on me in Shenandoah. In other words, they are going to be around during your entire hike, but they will probably be worse Late-May through Early-August.

Signs of Lyme Disease

Check out the Centers for Disease Control's web site for more information, but I'll give you a summary. One of the first signs that you have contracted Lyme Disease, which will normally occur 1 to 2 weeks after infection, is the development of a bullseye-shaped rash around the bite, although sometimes there won't be a rash at all. Lack of energy is another common first symptom, but you'll feel that on your hike either way. Other symptoms include fever, chills, headache, stiff neck, swollen lymph nodes, muscle pain, and joint pain.

If you do have symptoms, see a doctor as soon as possible. The longer you go without treatment, the worse symptoms will get and it can get incredibly nasty. If you find a bullseye-shaped rash or feel symptoms of the flu, get checked. If you do pull a tick off your body save it in a Ziploc bag so it can be tested later if symptoms do appear.

Mosquitoes and Black Flies

Even though, you could hike the entire Appalachian Trail without seeing a tick, mosquitoes may become the bane of your existence. I doubt you'll have much trouble with black flies, since they are worst in Maine from Mid-April through Mid-June.

Prevention

There will be days where this seems like an impossible task. There is no way to keep all mosquitoes at bay, but you can prevent them from driving you crazy.

Bug repellent

As I said previously, the most effective bug sprays on the market contain 23% to 33% DEET. Several studies, and my own personal experience, have shown that a higher concentration is basically just as effective. I also use Permethrin on clothes, but more on that in a bit.

I used to carry a 1 oz. eyedropper of 100% DEET oil, but sprays seem to be more effective. The eyedropper is ultralight, but this is where I'll sacrifice a couple ounces. Your happiness and sanity do have value after all. Many people use the eyedropper method by putting a few drops on the back of their neck, lower legs, wrists, and other strategic places, but it is believed that DEET works by surrounding you in a vapor that disrupts the bug's ability to sense humans and other animals. In my opinion, a few drops here and there just don't seem to create enough of this vapor barrier. Some people attract mosquitoes more than others, though, so my experience may not be the same as someone else's. I draw them in like I'm their mecca.

When using DEET, avoid getting it in your eyes, ears, nose, or on water bottles and food. Also, DEET can dissolve certain plastics, rayon, spandex, and other synthetic fabrics such as the lining in some raincoats. Be careful not to get it on the palms of your hands, so you don't ruin any gear. Since ticks and mosquitoes aren't much of a concern during a rainstorm, wipe any DEET off your skin that may come in contact with the lining of your rain gear before putting it on. A gear expert said DEET was the reason my Marmot raincoat lining was peeling off.

Is DEET safe?

DEET sounds horrible, right? After all, it can breakdown certain plastics and synthetic materials. You’re probably thinking, why would I want to put something like that on my skin?! Well, Vodka, vinegar, and Coca-Cola can dissolve a number of things too, but they won’t harm your skin.

It’s not hard to find someone who believes anything unnatural is going to kill you slowly, but if used properly DEET is safe. Of course, nothing is 100% safe, but don’t forget we are using them to avoid things like Lyme Disease, Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever, and West Nile Virus, which are far worse.

That said, using it properly is not always convenient on a long distance trail. For example, using it properly means you need to wash it off your skin at the end of the day. Since showers are rare on the AT, and since you don’t want to get DEET in the aquatic ecosystem, you’ll need to go at least 200 feet from a water source to rinse it off. Since mosquitoes are only a problem in warm weather, you won't have to worry about rinsing off when it's dangerously cold. Also, rinsing off is a good practice anyway since cleaning up at the end of the day will make you feel, smell, and sleep better.

Another potential concern is that most people aren't using DEET heavily for 5 months in a row, so I'm not sure long-term exposure has been thoroughly tested. It wouldn't surprise me if regular long-term use had some negative health effects, so I try to use it in moderation and sometimes switch to a less effective non-DEET repellent when mosquitoes aren't as bad. I'm not suggesting these non-DEET sprays are healthier, but I feel like it can't hurt to avoid using too much of any one chemical.

Non-DEET Repellents

Non-DEET Repellents

Permethrin – Prior to hiking in tick or mosquito season, I apply Permethrin to my clothes. This is not to be used on skin, but it can be effective on clothes for weeks even after numerous washes. If you’re in a buggy area, consider reapplying after about six washes. Of course, follow all directions on the bottle.

Lemon Eucalyptus – Don’t let the name fool you, just because something is natural, that doesn't mean it’s 100% safe. All the same safety rules apply with all bug repellents. It won’t damage plastics like DEET, but it also doesn't last as long. I found it to be nearly as effective as DEET-based repellents for about 15-30 minutes then starts to wear off quickly, whereas DEET is effective for five hours or more.

Picaridin is another pesticide that does not damage plastics, but its effectiveness seems to be about the same as Lemon Eucalyptus.

Picaridin is another pesticide that does not damage plastics, but its effectiveness seems to be about the same as Lemon Eucalyptus.

One final tip, apply sunscreens before applying bug sprays.

Home-remedies

I've heard of several home remedies for repelling ticks and mosquitoes, but at best, they only work for a few minutes and are not even that effective to begin with. I've heard of using dryer sheets, Vaporub, vanilla, smoke, garlic, vitamin pills, or other odor-masking items ingested or rubbed onto the skin. One I hear about often is Avon Skin-So-Soft, but it’s effectiveness only lasts about ten minutes whereas DEET can last five hours.

One reason that simply masking your odor doesn't work is that odor is not the only way mosquitoes detect humans. The primary way is from our exhaled carbon dioxide, which they can detect up to 100 feet way. They can also detect sweat, moisture, body heat, and lactic acid.

If someone wants to cover themselves in moose dung and spaghetti-os to repeal mosquitoes and ticks, be my guest, but we are talking about preventing horrible diseases and maintaining a certain level of enjoyment and sanity in the outdoors. Until something proves to be as effective and safe as DEET, I’ll keep doing what I’m doing.

If someone wants to cover themselves in moose dung and spaghetti-os to repeal mosquitoes and ticks, be my guest, but we are talking about preventing horrible diseases and maintaining a certain level of enjoyment and sanity in the outdoors. Until something proves to be as effective and safe as DEET, I’ll keep doing what I’m doing.

Mosquito Netting

This is the only effective non-chemical way to repeal mosquitoes that I'm aware of.

Poisonous Plants

VM: Can poisonous plants keep spreading if contacted with the rest of your gear?

I’m not the best source for this question, because I believe I’m one of the lucky immune few, so I haven’t done a lot of research on the subject.

Nevertheless, the answer is yes. It is possible for the plant oils that cause the allergic reaction, called urushiol, to get on your gear and spread to other people or other parts of your body. You have to come in contact with the urushiol, however, to have the allergic reaction.

Once you have rinsed the affected area of your skin, you’ll no longer be able to spread it. It can stick to gear pretty well though, and may still be able to cause an allergic reaction a year later. Washing the gear with a grease-cutting soap is probably your best bet. Dawn Dish Soap is the cheapest and easiest to find on the trail.

Of course, it’s best to avoid it in the first place. Learn to identify the plants. Remember the old adage, “Leaves of three, leave them be.” That’s a good place to start as leaves on both Poison Ivy and Poison Oak have three leaflets.

Also watch out for any plants with: shiny leaves, hairy leaves or stems (check under the leaf as well), or any plant with red stems, twigs, branches, or red hairy vines. Also avoid any plant that has a milky sap, umbrella-like flower, or pungent smell.

If walking through an overgrown area, wear long sleeves and pants. If you're highly allergic, consider carrying an ivy block barrier.

For more information on this topic, please check out the poison ivy page at the American Academy of Dermatology web site.

Other Pests

Snakes

I only saw one venomous snake on the Appalachian Trail. I nearly stepped on a Timber Rattler in near Delaware Water Gap. I was on Rattlesnake Mountain at the time, so I guess it shouldn't have been a surprise.

I'm not a snake expert, but you can prevent confrontations by avoiding tall grass, watching your step, and checking before you stick your hand into a crevasse. If you're cowboy camping under the stars, avoid sleeping near their territory: beside a log, in tall grass, or along rock crevasses. Keep your tent zipped up when you're not around.

Shelter Rodents

Shelter Rodents

Other than mosquitoes, the most common annoyance with pests on the trail is the theft of food and the damage done to your gear when they are trying to get to your food. Not just shelter rodents, but bears, porcupines, possums, and raccoons as well. This is preventable though.

Nearly every shelter will have ropes on the ceiling to hang your food. They'll have something like a tin can halfway up the rope to keep rodents from crawling down to your food bag. Always use these or hang your food in a tree or bear pole.

Nearly every shelter will have ropes on the ceiling to hang your food. They'll have something like a tin can halfway up the rope to keep rodents from crawling down to your food bag. Always use these or hang your food in a tree or bear pole.

If you leave your gear behind even for a few minutes, something might come by and chew a hole into your backpack. This happened to me on the Wonderland Trail. If you set your pack down for an extended amount of time, carry your food with you. I use a homemade drawstring backpack for food now, so I can easily carry it with me if I want to leave my gear behind while I go down a side trail or summit a mountain.

Black Bears

Black Bears

This could be it's own post, but I'll be brief. I don't generally classify a bear as a pest, but I do classify anything that can rip open your pack and eat your food as a pest. To prevent issues, remember these simple rules...

Black Bears (which are the only bears you will encounter on the AT) are very skittish and will generally run away if they hear you coming. Don't surprise them though, or they may react defensively. Before turning a corner, or cresting a hill, make noise by singing or talking. Bear bells or clicking your trekking poles together might have some effect, but are not as effective as the human voice.

When camping in bear country, hang your food and other scented items from a tree or bear pole at least ten feet above the ground. Never cook or store food near your tent and keep a clean camp or shelter.

The highest concentration of bears on the Appalachian Trail is in the Delaware Water Gap area (around the border of New Jersey and Pennsylvania) and Shenandoah National Park, so be extra cautious in those locations.

For more information and what to do if you encounter a Black Bear, check out the National Park Service's bear safety tips.

More Q&As with Victor:

Weather and Morale on the Appalachian Trail

Shelters Vs. Tents on the Appalachian Trail

Knives on the Appalachian Trail

Hiking with Visitors on the Appalachian Trail

Online Mail Drops on the Appalachian Trail

First, let me just remind you that Victor's hike begins this Thursday (March 28th), join me in following his progress at BackpackingAT.com.

VM: From what I hear, knowledge is power. Is it true that learning how to prevent visitors is half the battle, or is it inevitable?

RG: Yes and yes. There are ways to reduce potential issues with the bugs and wildlife, but it comes with the territory. There are different guidelines for different pests that I’ll go into below.

Ticks

TicksVM: Do you have any useful hints for removing ticks? Is it true a drop of turpentine will make the ticks dig themselves out?

RG: Good question. Ticks are the worst. I'd honestly rather see a black bear on the trail (actually I love seeing black bears, so that's a bad example). I only saw two ticks crawling on me while hiking the AT, but I also met two hikers who contracted Lyme Disease, so it's good to know a few things about them before heading out.

There are several myths about tick prevention and removal. Using heat or covering the tick with anything in order to coax it back out can only make the problem worse. It can actually cause them to regurgitate more saliva (and potentially more pathogens) into your bloodstream.

The hypostome, i.e. mouth parts, that they burrow into your skin, looks similar to a tiny barbed harpoon. Also, some ticks, like the Lyme-Disease-spreading deer tick, secrete a cement-like substance to keep themselves securely attached to your skin while feeding. In other words, they can't back out quickly even if they wanted to. The longer the tick is attached, the higher your risk of infection, so the goal is to remove the tick as soon as possible.

The best way to remove a tick

The best way is with tweezers. Some ticks, like the Deer Tick, can be as tiny as a poppy seed, so you’ll need tweezers that can grab something that small. Grab the tick as close to your skin as possible and slowly pull it straight out. Clean the skin around the bite with alcohol. If the hypostome (mouthparts) remain stuck in your skin, don’t worry about it. Doctors aren't concerned about it, so I'm not either. Also, when the hypostome breaks it may even send germs and saliva further back into the ticks body and saliva glands.

Lyme Disease

The biggest concern with ticks on the Appalachian Trail is Lyme Disease. There are 30,000 to 40,000 cases in the United States annually and about three out of four are reported in ten of the states along the Appalachian Trail.

Here they are in order of highest cases per capita: Vermont, New Hampshire, Maine, Connecticut, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Massachusetts, Maryland, New York, and Virginia.

Here they are in order of highest cases per capita: Vermont, New Hampshire, Maine, Connecticut, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Massachusetts, Maryland, New York, and Virginia.If you experience any symptoms like a rash or fever, consult your doctor and let them know you've been bitten.

Preventing Ticks

Chances are you'll hike the entire Appalachian Trail without having a tick burrow into you, but with a few precautions, you can reduce your risk of getting Lyme Disease to nearly zero.

Do a daily tick check

Full disclosure, the longer I went without seeing a tick the less frequently I would do a tick check. Eventually, I only checked after hiking through bushy areas with tall grass or loose dry leaves on the ground. My laziness aside, daily checks are by far the best way to prevent the spread of Lyme Disease. It generally takes at least 24-48 hours for a tick to transmit the disease, so if you're doing daily checks, it's unlikely you'll get it.

Thorough tick checks are important since their saliva has anesthetic properties. That means you won't feel them burrowing or feeding. Additionally, they are hard to find because some, like the deer tick, are as small as a fleck of dirt, which you'll be covered in most of the time. They also have a tendency to search for places on your body that are hard to see without a mirror... and places your friends will not volunteer to check for you.

Bug Repellent

I'll go into this deeper below, but DEET is still the most effective bug repellent. Nothing really comes close in effectiveness, duration of effectiveness, and cost per ounce. There are a lot of home remedy bug repellent myths out there, but none have been shown to be effective for more than a few minutes, if effective at all. Don't waste your time or risk going without an effective treatment. A 23 to 33% DEET solution is the way to go and it's safe if used properly.

Wear Light Colored Clothing

Even though I didn't have any biting ticks on the Appalachian Trail, I did find a couple crawling on my pant legs. It happened after scouring the woods for firewood in Shenandoah National Park. Since I wore light brown khaki pants they were easy to spot.

Walk in the center of trails

Those minuscule SOBs are hanging onto plants with their little legs outstretched waiting for a blood-filled mammal to walk by. Avoid their reach by walking down the center of the trail whenever possible.

Some months are worse than others

Peak tick season starts in late-April to early-May and lasts all through summer. That doesn't mean you won’t get ticks on you in October, though. Actually, that's when I found them on me in Shenandoah. In other words, they are going to be around during your entire hike, but they will probably be worse Late-May through Early-August.

Signs of Lyme Disease

Check out the Centers for Disease Control's web site for more information, but I'll give you a summary. One of the first signs that you have contracted Lyme Disease, which will normally occur 1 to 2 weeks after infection, is the development of a bullseye-shaped rash around the bite, although sometimes there won't be a rash at all. Lack of energy is another common first symptom, but you'll feel that on your hike either way. Other symptoms include fever, chills, headache, stiff neck, swollen lymph nodes, muscle pain, and joint pain.

If you do have symptoms, see a doctor as soon as possible. The longer you go without treatment, the worse symptoms will get and it can get incredibly nasty. If you find a bullseye-shaped rash or feel symptoms of the flu, get checked. If you do pull a tick off your body save it in a Ziploc bag so it can be tested later if symptoms do appear.

|

| (Photo: I forgot bug spray on a trip in Southern Indiana) |

Even though, you could hike the entire Appalachian Trail without seeing a tick, mosquitoes may become the bane of your existence. I doubt you'll have much trouble with black flies, since they are worst in Maine from Mid-April through Mid-June.

Prevention

There will be days where this seems like an impossible task. There is no way to keep all mosquitoes at bay, but you can prevent them from driving you crazy.

Bug repellent

As I said previously, the most effective bug sprays on the market contain 23% to 33% DEET. Several studies, and my own personal experience, have shown that a higher concentration is basically just as effective. I also use Permethrin on clothes, but more on that in a bit.

I used to carry a 1 oz. eyedropper of 100% DEET oil, but sprays seem to be more effective. The eyedropper is ultralight, but this is where I'll sacrifice a couple ounces. Your happiness and sanity do have value after all. Many people use the eyedropper method by putting a few drops on the back of their neck, lower legs, wrists, and other strategic places, but it is believed that DEET works by surrounding you in a vapor that disrupts the bug's ability to sense humans and other animals. In my opinion, a few drops here and there just don't seem to create enough of this vapor barrier. Some people attract mosquitoes more than others, though, so my experience may not be the same as someone else's. I draw them in like I'm their mecca.

When using DEET, avoid getting it in your eyes, ears, nose, or on water bottles and food. Also, DEET can dissolve certain plastics, rayon, spandex, and other synthetic fabrics such as the lining in some raincoats. Be careful not to get it on the palms of your hands, so you don't ruin any gear. Since ticks and mosquitoes aren't much of a concern during a rainstorm, wipe any DEET off your skin that may come in contact with the lining of your rain gear before putting it on. A gear expert said DEET was the reason my Marmot raincoat lining was peeling off.

Is DEET safe?

DEET sounds horrible, right? After all, it can breakdown certain plastics and synthetic materials. You’re probably thinking, why would I want to put something like that on my skin?! Well, Vodka, vinegar, and Coca-Cola can dissolve a number of things too, but they won’t harm your skin.

It’s not hard to find someone who believes anything unnatural is going to kill you slowly, but if used properly DEET is safe. Of course, nothing is 100% safe, but don’t forget we are using them to avoid things like Lyme Disease, Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever, and West Nile Virus, which are far worse.

That said, using it properly is not always convenient on a long distance trail. For example, using it properly means you need to wash it off your skin at the end of the day. Since showers are rare on the AT, and since you don’t want to get DEET in the aquatic ecosystem, you’ll need to go at least 200 feet from a water source to rinse it off. Since mosquitoes are only a problem in warm weather, you won't have to worry about rinsing off when it's dangerously cold. Also, rinsing off is a good practice anyway since cleaning up at the end of the day will make you feel, smell, and sleep better.

Another potential concern is that most people aren't using DEET heavily for 5 months in a row, so I'm not sure long-term exposure has been thoroughly tested. It wouldn't surprise me if regular long-term use had some negative health effects, so I try to use it in moderation and sometimes switch to a less effective non-DEET repellent when mosquitoes aren't as bad. I'm not suggesting these non-DEET sprays are healthier, but I feel like it can't hurt to avoid using too much of any one chemical.

Non-DEET Repellents

Non-DEET RepellentsPermethrin – Prior to hiking in tick or mosquito season, I apply Permethrin to my clothes. This is not to be used on skin, but it can be effective on clothes for weeks even after numerous washes. If you’re in a buggy area, consider reapplying after about six washes. Of course, follow all directions on the bottle.

Lemon Eucalyptus – Don’t let the name fool you, just because something is natural, that doesn't mean it’s 100% safe. All the same safety rules apply with all bug repellents. It won’t damage plastics like DEET, but it also doesn't last as long. I found it to be nearly as effective as DEET-based repellents for about 15-30 minutes then starts to wear off quickly, whereas DEET is effective for five hours or more.

Picaridin is another pesticide that does not damage plastics, but its effectiveness seems to be about the same as Lemon Eucalyptus.

Picaridin is another pesticide that does not damage plastics, but its effectiveness seems to be about the same as Lemon Eucalyptus.One final tip, apply sunscreens before applying bug sprays.

Home-remedies

I've heard of several home remedies for repelling ticks and mosquitoes, but at best, they only work for a few minutes and are not even that effective to begin with. I've heard of using dryer sheets, Vaporub, vanilla, smoke, garlic, vitamin pills, or other odor-masking items ingested or rubbed onto the skin. One I hear about often is Avon Skin-So-Soft, but it’s effectiveness only lasts about ten minutes whereas DEET can last five hours.

One reason that simply masking your odor doesn't work is that odor is not the only way mosquitoes detect humans. The primary way is from our exhaled carbon dioxide, which they can detect up to 100 feet way. They can also detect sweat, moisture, body heat, and lactic acid.

If someone wants to cover themselves in moose dung and spaghetti-os to repeal mosquitoes and ticks, be my guest, but we are talking about preventing horrible diseases and maintaining a certain level of enjoyment and sanity in the outdoors. Until something proves to be as effective and safe as DEET, I’ll keep doing what I’m doing.

If someone wants to cover themselves in moose dung and spaghetti-os to repeal mosquitoes and ticks, be my guest, but we are talking about preventing horrible diseases and maintaining a certain level of enjoyment and sanity in the outdoors. Until something proves to be as effective and safe as DEET, I’ll keep doing what I’m doing. Mosquito Netting

This is the only effective non-chemical way to repeal mosquitoes that I'm aware of.

Poisonous Plants

VM: Can poisonous plants keep spreading if contacted with the rest of your gear?

I’m not the best source for this question, because I believe I’m one of the lucky immune few, so I haven’t done a lot of research on the subject.

Nevertheless, the answer is yes. It is possible for the plant oils that cause the allergic reaction, called urushiol, to get on your gear and spread to other people or other parts of your body. You have to come in contact with the urushiol, however, to have the allergic reaction.

Once you have rinsed the affected area of your skin, you’ll no longer be able to spread it. It can stick to gear pretty well though, and may still be able to cause an allergic reaction a year later. Washing the gear with a grease-cutting soap is probably your best bet. Dawn Dish Soap is the cheapest and easiest to find on the trail.

Of course, it’s best to avoid it in the first place. Learn to identify the plants. Remember the old adage, “Leaves of three, leave them be.” That’s a good place to start as leaves on both Poison Ivy and Poison Oak have three leaflets.

Also watch out for any plants with: shiny leaves, hairy leaves or stems (check under the leaf as well), or any plant with red stems, twigs, branches, or red hairy vines. Also avoid any plant that has a milky sap, umbrella-like flower, or pungent smell.

If walking through an overgrown area, wear long sleeves and pants. If you're highly allergic, consider carrying an ivy block barrier.

For more information on this topic, please check out the poison ivy page at the American Academy of Dermatology web site.

|

| (Photo: Unidentified Snake) |

Snakes

I only saw one venomous snake on the Appalachian Trail. I nearly stepped on a Timber Rattler in near Delaware Water Gap. I was on Rattlesnake Mountain at the time, so I guess it shouldn't have been a surprise.

I'm not a snake expert, but you can prevent confrontations by avoiding tall grass, watching your step, and checking before you stick your hand into a crevasse. If you're cowboy camping under the stars, avoid sleeping near their territory: beside a log, in tall grass, or along rock crevasses. Keep your tent zipped up when you're not around.

Shelter Rodents

Shelter Rodents Other than mosquitoes, the most common annoyance with pests on the trail is the theft of food and the damage done to your gear when they are trying to get to your food. Not just shelter rodents, but bears, porcupines, possums, and raccoons as well. This is preventable though.

Nearly every shelter will have ropes on the ceiling to hang your food. They'll have something like a tin can halfway up the rope to keep rodents from crawling down to your food bag. Always use these or hang your food in a tree or bear pole.

Nearly every shelter will have ropes on the ceiling to hang your food. They'll have something like a tin can halfway up the rope to keep rodents from crawling down to your food bag. Always use these or hang your food in a tree or bear pole.If you leave your gear behind even for a few minutes, something might come by and chew a hole into your backpack. This happened to me on the Wonderland Trail. If you set your pack down for an extended amount of time, carry your food with you. I use a homemade drawstring backpack for food now, so I can easily carry it with me if I want to leave my gear behind while I go down a side trail or summit a mountain.

Black Bears

Black BearsThis could be it's own post, but I'll be brief. I don't generally classify a bear as a pest, but I do classify anything that can rip open your pack and eat your food as a pest. To prevent issues, remember these simple rules...

Black Bears (which are the only bears you will encounter on the AT) are very skittish and will generally run away if they hear you coming. Don't surprise them though, or they may react defensively. Before turning a corner, or cresting a hill, make noise by singing or talking. Bear bells or clicking your trekking poles together might have some effect, but are not as effective as the human voice.

When camping in bear country, hang your food and other scented items from a tree or bear pole at least ten feet above the ground. Never cook or store food near your tent and keep a clean camp or shelter.

The highest concentration of bears on the Appalachian Trail is in the Delaware Water Gap area (around the border of New Jersey and Pennsylvania) and Shenandoah National Park, so be extra cautious in those locations.

For more information and what to do if you encounter a Black Bear, check out the National Park Service's bear safety tips.

More Q&As with Victor:

Weather and Morale on the Appalachian Trail

Shelters Vs. Tents on the Appalachian Trail

Knives on the Appalachian Trail

Hiking with Visitors on the Appalachian Trail

Online Mail Drops on the Appalachian Trail

A Backpacker's Life List by Ryan Grayson is licensed under a

Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License.

com-s.jpg)

com-s.jpg)

com-s.jpg)

com-s.jpg)